“Men are only as good as their technical development allows them to be.” –George Orwell

The modern consumer has taken a much more active role in corporate policy development and direction than in decades past. “Vote with your dollar” campaigns and boycott movements have gone from mosquitoes to hurricanes, forcing dramatic shifts in how investors and corporate executives navigate change and interact with their customers. While social and environmental issues were once considered both opaque and risky, they are now front and center in every conversation about our new digital economy’s future. Though many activist discussions used to be reserved for the camps of Occupy Wall Street, it is clear that a monumental shift has occurred. Impact investing has manifested itself as the logical market response to a rapidly growing cohort of consumers that expect higher ethical standards from the businesses and institutions they support.

After almost two decades of innovation, seemingly for innovation’s sake, the digitally transformed economy so many yearned for seems to be within reach. Activated like a bolt of lightning by the global pandemic, this transformation reaches further into citizens’ daily lives than anyone, save maybe Orwell, could have ever imagined. Whether or not this new digital economy will serve the best interests of humanity will be a question answered by the actions of citizens and corporations alike. It is no longer a debate; we are living through an era of enlightenment many futurists and forward-looking evangelists have spent decades preparing us for. It is essential to take a moment to recognize this prescience, take a step back, and examine how we got here.

There aren’t many people more qualified to help the world understand this historical trajectory than Jim Whitehurst, president of IBM, former CEO of Red Hat, and possibly most influential proponent of open-source computing in history. Whitehurst led Red Hat to become the first $1B open-source software company, seven years before being acquired by IBM in 2019 for $34B the single largest acquisition in IBM’s 110-year history.

IBM Headquarters. Photo courtesy IBM.

Sitting at your desk, either from home or in Armonk, New York, what do you see on the horizon? Conversely, what do you believe we should leave in the rear-view mirror as we create this post-pandemic economy?

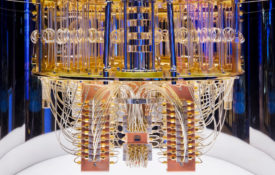

One of the things that we’re working on right now at IBM is generative modeling. You take hundreds of thousands of different elements and materials, run them through models, and know all those models’ characteristics. We can now, especially using the power of quantum computing, start to go back and say, “I’m looking for a material that might attract carbon out of the atmosphere onto what’s the substrate.” And rather than trying to figure out what it is, say, “Hey, I know all these characteristics of all of these, what might the material be that does that?” and that ability, not just to do that deductive stuff that we can do now, but the more generative property, can be incredible.

We announced, and I had to be the one to announce it because I’m passionate about it, that IBM is committing to carbon neutrality by the year 2030. But what we said is, “We’re not going to do that by buying offsets; we’re going to get most of the way there by using less energy. But the rest that we can’t, we’re going to get there through technology advancement. We can see a pathway to get there with what we know, and it’s an inspiring initiative to be a part of.”

I would say what scares me the most right now is way too much data floating around, even encrypted, and people seem to think that’s okay, combined with the fact that we know in five years, quantum computers will be out there. What I mean by that is data stolen today that you say, “Well, that’s OK, it’s heavily encrypted.” If it’s not quantum-safe encryption, which very little is now out in use, somebody can harvest that in five years, and they’re going to get the data. People’s medical records, financial records, you know, in five years, they still have much value when someone might be able to decrypt them.

So thinking ahead of the curve now and recognizing there will be quantum encryption because we have it now, we’ve all announced road maps. Most of the technologies we use now for encryption will be obsolete. It’s not a problem when they exist; it’s a problem on the data right now that somebody can take and harvest and warehouse for later use. That’s the thing that probably scares me more than anything else.

On that point, I do think that I’ve lived this from the open-source world, where information by its nature is free. In the sense it’s abundant and that it’s virtually freely copyable. People who are generating information content as a business realized that was a bug. So, they kind of created models, patents, and copyrights to take something that wasn’t scarce and make it scarce.

We haven’t yet figured out a public policy answer to all of this information that is out there. Companies, if you can grab it, it’s like, “Well, hey, it’s mine, I can grab it.” Well, do we need something like the equivalent of copyright or whatever that would be? Where you say, “No company, just because you can freely garner it from someone who, unbeknownst to them, is giving to you, does that mean you really can have full ownership over that or not?” With this idea of abundance, we solved it in different ways, proprietary software via copyrights and open source via a different set of copyrights that cause them to be open. But how do we solve that for other types of information, especially consumer information where just because somebody can grab it for free, does that really mean that they are allowed to own it, use it? And those are important public policy questions that will get to the heart of our democracy in our society that we’re going to have to address over the coming decades.

What place do you see IBM holding in the marketwide shift toward more ethical and harmonious business practices related to environmental, social, and governance trends?

I think it’s just all about “time horizon.” One of the reasons you hear me talking about that and IBM talking about it is we’ve been around for over 100 years. IBM issued its first climate report in 1970. We published our first kind of environmental report in 1990. We had four different carbon goals, with the last one getting us to zero. If you’re going to live in a society, if you’re going to be a successful business, you have to live in a healthy community.

And that’s healthy in multiple regards. That’s whether it’s making sure that consumers can afford to live and therefore have a thriving economy. So I’m not sure that requires a B corp. I think that it needs recognizing that if we’re building businesses for the long run, that means building them in a healthy context, right?

Being a creature in a dying forest doesn’t help the creature. So, for companies, we all need to have that as a perspective. We should measure it, and we should hold ourselves accountable for it. Let us be public about those things. We have been on things like the environment and diversity, trying to gather more data.

If we can put that data out there, consumers will hold us accountable for it in the decisions that they make, which even helps with the short-term numbers. I think it’s more a sense of “time horizon” versus confusion around purpose. I’m not trying to say I know many companies can get so short-term quarterly focused. If you have a board and a leadership team that’s thinking about how am I building an institution for the long run? That helps.

At Red Hat, I was there longer, and I spent a lot of time talking about if you look at software companies, there are not that many software companies that have had multiple serial successes. You get companies to have one victory, and then they bought a bunch of stuff. For Red Hat and IBM has done this, REL was awesome. But we need to think hard about what capabilities we are building in our culture that will let us have the next thing.

The next big one, not to trivialize the other projects, was OpenShift. I think that started with, “If we’re trying to build an institution that lasts forever …” Then you start thinking about things like, “Well, what capabilities am I building?” “How do I attract the right people that I can kind of persist this going forward?” It’s hard to do that without starting to think about whether that’s the environment, whether that’s about diversity, about all of the core issues that ultimately make up a healthy society in which we can thrive. So, I think it’s more “horizon” versus a different objective for the corporation itself.

2010 Red Hat Summit. Photo curtesy Red Hat.

We are reaching a volatile time where increased attention will be focused on markets, how they work, and whom they serve. Are we prepared? What have you learned that’s going to help us?

I got a degree in computer science and economics from Rice University. I thought at the time—I laugh, now, when I say this—I thought I would be CEO of a technology company. Then I ultimately took a U-turn. I had no idea what I wanted to do when I graduated. I just started shoving résumés into folders—this was 1989, before it was all electronic—and interviewed. The person I clicked the best with was the person interviewing at Rice from the Boston Consulting Group, BCG, and their Chicago office. I’m from Columbus, Georgia, and I went to school in Houston, Texas; I barely ever saw snow.

So, I took a job for BCG in Chicago. You can imagine the type of clients around Chicago, much more kind of industrial oriented, it’s a fair amount of consumer product, so I did almost no tech. I did a bunch of other things but loved it. They sent me back to business school. So, I went to [Harvard Business School] and came back to BCG and thought I would never leave, and I don’t think I would have if I stayed if I was a partner there. I did move back to the Atlanta office soon after BCG opened the Atlanta office.

My biggest client was Delta Airlines. At noon on 9/11, the CEO called me and said, “I need you right now.” So, I became treasurer of Delta Airlines at noon on 9/11. They desperately needed me. They were big clients, so I knew them. I was there that day. Ultimately, I made it official a couple of months later. I took the dustcover off the treasurer’s desk because it was an open position there and started thinking about how we were going to not go bankrupt.

There was a cultural thing at BCG, where you would go either fly to a client, you’d see a client, you get to the airport, you’d all be getting out of a taxi. It is then a mad dash to the gate because whoever got to the gate first was going to get the upgrade. It didn’t matter whether it was the senior partner or the first-year associate out of college; whoever got there first got the promotion. BCG was the first place I’d ever worked; I didn’t realize things could be different. It certainly colored my early days with the importance of really hearty debate and tried to break down the trappings of authority that can slow that down.

Then I got to Delta, which was the exact opposite, in a significant way. Delta’s a wonderful company. Airlines grew out of military culture. So many people are military and live on campus at Delta. At the front gate, they would salute when I drove on. Very different world, but an extraordinary experience. At the same time, we talked a lot at Delta about how we were way too nice. One of the things that we tried to break through was to drive a little bit more candor in our discussions to make sure that we talked about the challenging issues. So that was an interesting cultural challenge there.

I started running treasury and business development, ultimately became COO, which had almost everything reporting to me. Marketing, sales network, everything. I look back on it now, and it’s kind of crazy. I was 35 years old when they promoted me to that role and executed through the bankruptcy, making it to the other side. A new board was formed. I reason so: the new board wanted to choose their own CEO and chose someone external—Richard Anderson, whom I have much respect for. I knew him from back in the days when he was at Northwest.

Honestly, I had no idea what I was going to do next. While I was at Delta, I was trying to do the analysis myself. I spent nights and weekends on the network. This massive amount of data can be downloaded because airlines still have this kind of holdover, a regulatory filing requirement from back when airlines were regulated. Every 10th ticket is sampled and sent to the US government, who then puts that out in an electronic form. I would download all this data because the nice part is reading granular ticket data, and you can see many behaviors around it.

The problem was to have a year’s worth of that ticket tear data that you can then do polls from was more than four gigabytes. Those of us who are older in technology will remember the FAT file system had a four-gigabyte file size limit, so it was too big for that. That wasn’t true with the EXT with the EXT2 file system at the time with Linux.

So, I started using Linux to analyze the data because I could have a bigger file size to do the stuff I wanted. I had a degree in computer science; even though I hadn’t used it in my career, I was still pretty techie. After I left Delta, mainly getting calls from more significant, more industrial companies, I got this call about Red Hat. I remember the recruiter saying, “You probably never heard of this company. It’s called Red Hat. I say, “Are you kidding? I’m using Fedora at home!” Fedora is a free version of Red Hat Linux.

I came and met the CEO who’s looking to retire, and it just kind of clicked, and so that’s how I ultimately ended up at Red Hat. I do think part of it was I knew technology. When you’re in the airline industry, there are many wonderful things about large network carriers, and they connect the world. But I have to say part of you is jealous of the Southwests and the JetBlues. The simple business models came in with a very just different way to operate and take share and be kind of the upstart.

That’s the fantastic thing about Red Hat. When I joined at the very end of 2007, we were building a new business model. We talked about it a lot at the time; it’s transforming how technology is built and consumed. Open source on how you build the technology, and then you get to create a new business model because you can’t sell a license if you don’t have a license.

And so, it was enjoyable to all of a sudden go from being part of kind of the establishment defending against attackers in the airline business to being at Red Hat, where all of a sudden, we got to be the attacker. There’s something magical about that in the sense of it’s kind of fun to attack. But your ability to pivot because of its size, and you’re not as entrenched in one way of doing things, was an extraordinary experience.

Tomorrow: More open-source; AI; the cloud; and much more. Read the second and final part of the conversation.

This article was transcribed from a podcast conversation between Jim Whitehurst and Michelle Dennedy on the April 10, 2021, episode of Smarter Markets by Abaxx Technologies (abaxx.tech). To listen to the conversation in its entirety, visit smartermarketspod.com.