An implant that enables deaf people to hear. A prosthetic retina that helps blind people see. A device that allows amputees to control prosthetic fingers with their brains. These are just a few of the inventions created by the 17 companies that Alfred E. Mann has led over the course of his lifetime.

And he’s not stopping there. The tenacious billionaire is now betting his legacy and fortune on a new product called Afrezza.

Approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2014, Afrezza allows diabetics to inhale insulin instead of injecting it. A quick puff replaces an injection at meal time. It’s a potential game changer for the 29 million diabetics in the United States.

Mann’s invention has the power to disrupt the pharmaceutical industry in the same way Uber supplanted taxicabs, and Netflix rendered the neighborhood video rental store obsolete. “Diabetes is the greatest health care problem facing the world today. We need to find a solution to that,” Mann says. “I’m excited because we are making a major contribution.”

Mann’s success isn’t driven by money. He is on a personal crusade to do whatever he can to help humanity, driven by

a deep desire to change the world.

The original members of the Alfred Mann Foundation in 1986: (left to right) Jerry Adomian, Al Mann, Joe Schulman, Dave Whitmoyer, Chuck Byers

…But He’s Not a Doctor

Born and raised in Portland, Oregon, Mann joined the Army after graduating from high school. He spent World War II behind a desk. Once the war came to an end, he moved to Southern California and earned a degree in physics from UCLA.

One of the most prolific inventors and entrepreneurs of his time, Mann set up companies that are worth more than $4B. The product lines are diverse. From missile guidance systems to cochlear implants, the majority of Mann’s companies have eradicated many of the medical conditions that have baffled scientists and doctors around the world – such as caring for amputees returning from wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and for patients suffering from irreversible heart conditions and diabetes. The ultimate irony, according to David Hankin, CEO of the Alfred Mann Foundation, is that Mann is not a physician; rather, he is a scientist with two degrees in physics. “He addresses problems from a very different perspective than a medical doctor would, and I think that’s why he’s been successful. I think he’s able to visualize different approaches to problems that are outside the norm,” says Hankin.

“Diabetes is the greatest health care problem facing the world today. We need to find a solution to that. I’m excited because we are making a major contribution.”

Mannkind’s newest innovation, the inhalable insulin Afrezza, was approved by the FDA in 2014 and launched in early 2015

Hankin, an entertainment industry veteran, describes Mann as passionate about creating solutions that will improve mankind. While that might sound like starry-eyed optimism, Hankin believes in Mann’s philosophy. The 89-year-old entrepreneur also pays great attention to detail with all of the companies in his portfolio, which often catches Hankin by surprise. At a meeting about the formation of a new venture, Hankin watched as Mann studied 35 pages of spreadsheets detailing a complex transaction. Mann interrupted five minutes later, claiming, “on page 17, line 4, column 8, there’s a mistake. And he was right!” adds Hankin.

Researching and licensing medical products has been the primary objective of the Alfred Mann Foundation since it formed in 1985. The Mann Foundation supervises the several Alfred Mann Institutes for biomedical engineering at the University of Southern California, Purdue University, and Technion in Israel. Mann’s foundation is also focused on maintaining the innovative corporate culture that has been a hallmark of his companies. “People are treated with dignity and respect in all of his organizations, and I think that’s why Al has such a great influence,” says Hankin.

Love at First Laugh

The warmth and equitable environment at Mann’s business ventures may be a result of the relationship Mann has with his fourth wife, Claude, at home. The couple, now married for 10 years, first met at one of Claude’s restaurants, L’Affair, in Northridge. During our conversation this spring, Claude said, “It was love at first laugh. I fell in love without seeing him. I love a man who can laugh.” In between his own chuckles, Mann said, “It was the best restaurant in the area and I got to be a very good customer.”

Inspired by Mann’s philanthropy, Claude created and has since led fundraising efforts for Mann’s foundation, including setting up an annual gala.

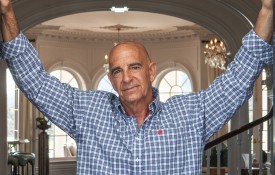

As he approaches his 90th birthday, Mann says it’s harder for him to continue to remember minute details on spreadsheets like he famously did a few years ago. He also has had to limit his love of travel to the United States. But he keeps working. Just don’t ask him about his legacy. “I don’t do anything specifically for a legacy,” he says pointedly.

Two of Mann’s siblings are classical musicians. Although Mann has invested in operas, symphonies, and music programs, his primary focus is to solve what he calls “unmet or poorly met” medical needs. And as a result, the foundation is the recipient of most of Mann’s fortune.

Mann hopes his foundation will continue to support his vision for changing the world long after he’s gone. “Money doesn’t have value unless you put it to use. You can only spend so much on yourself, so why not give it back to society?”

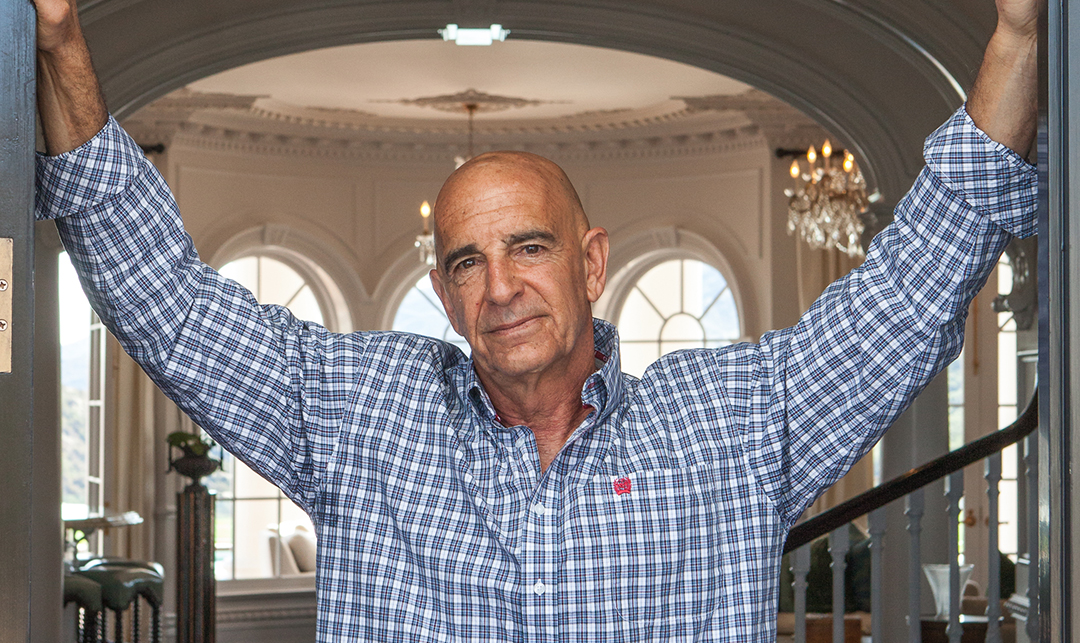

David Hankin, Alfred Mann, and Claude Mann in June 2015