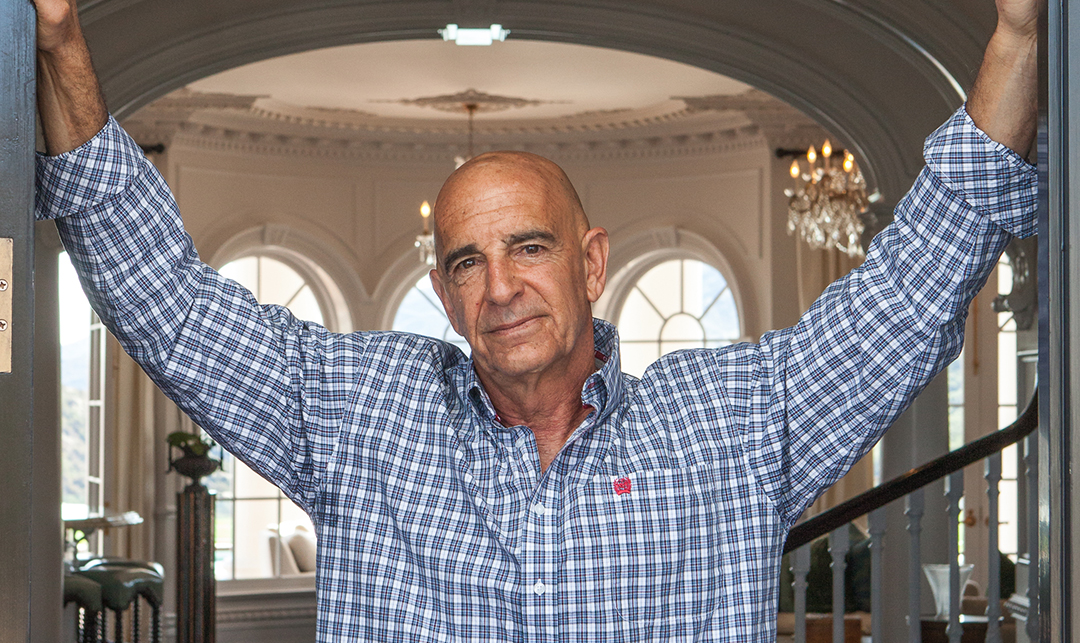

As new technologies brought sweeping changes to the financial industry over the past few years, Douglas Merrill saw that a substantial slice of the pie was left on the table, untouched. So he devised a recipe that incorporated the raw numbers.

“People were interested in using technology to change consumer credit, and banks were talking about it, but nothing was happening,” explains Merrill. He decided to apply the approach taken at Google; focus on infrastructure, and recognize that search is a math problem. According to Merrill, credit is also a math problem, one that can be eased by identifying and utilizing more data points. “The current credit system isn’t working because it’s limited by too little data. If even one piece of data is missing, it can drop a borrower from prime to subprime.” Enter ZestFinance, a provider of tools to banks and other financial institutions who want to offer fair and transparent credit to people underserved by the credit market. “There are many Americans who either can’t access credit, or only have access to expensive and abusive loans,” says Merrill.

He can relate to feeling ostracized. Growing up in a small Arkansas town, Merrill describes his primary childhood experience as “trying to be safe.” He is dyslexic, and was deaf from age 3 to 6 due to a treatable auditory nerve infection, which caused him to relearn to speak. Together, these two hurdles would form Merrill’s way of thinking about life. He wore his hair long and straggly and spoke with a Canadian accent picked up from his voice coach, things that were not helpful living in a minuscule town in Arkansas.

A Quick Study

“It always made me try to build a different way for myself, a way that played to my strengths rather than my weaknesses,” he explains. His feeling of ostracization forced him to think a lot, even as a child, about what he is good at and what he is not good at. Being a high school student in a small town made the list of things he decided he was not good at, so Merrill graduated from high school at 16 and college at 19.

“The current credit system isn’t working because it’s limited by too little data … there are many Americans who either can’t access credit, or only have access to expensive and abusive loans.”

Merrill’s parents were very supportive of education, but while they expected him to earn an advanced degree, the timing and speed of his education was a concern. Sending their 16-year-old son off to college at the University of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was made easier because his mother’s oldest friend worked there. At age 22, Merrill earned his Ph.D. from Princeton University.

He describes his experience as, “always playing the game by a different set of rules, and following the beat of a different drummer.” He illustrates this process by recalling his approach to math: “Instead of answering the equations in class, I would write stories about how the numbers worked together and how the numbers worked apart. I would never write a traditional math answer, because for me, telling stories is much more interesting.” With a propensity toward creating things, Merrill began making artificial intelligence machines, smart machines, while at Princeton. “We didn’t have much computational power or storage, because storage was very expensive so they were weak AI machines, but still, I did it because it was fun.”

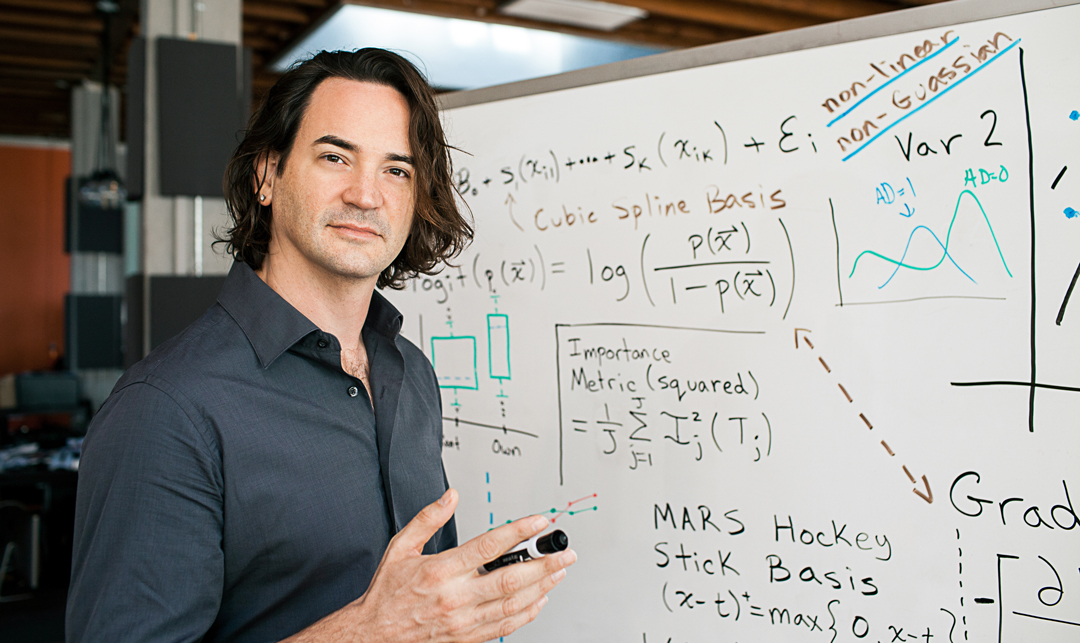

An inside look at ZestFinance’s creative workspace

Merrill’s extremely popular 1992 master thesis at Princeton, Effective Tutoring Techniques: A Comparison of Human Tutors and Intelligent Tutoring Systems, concerned the comparison of the guidance and support of human tutors with that provided by intelligent tutoring systems. Before leaving academia, Merrill and his co-author, who was at the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, solved the issue presented through their article and became friends. Soon after Princeton, that relationship was the path to Merrill working for RAND for four years, where he met Stephen Drezner, his first professional mentor. “I always try to find smart interesting people to learn from,” explains Merrill, reflecting that these relationships are part of a lesson the universe is trying to teach him. “Sometimes seemingly random relationships are valuable.”

Merrill is also a fan of executive coaching. “Olympic athletes have coaches, why shouldn’t executives have coaches?” His professional coach is Ed Batista, a professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business whom Merrill credits with both teaching skill and the expertise to notice and tick off themes that Merrill otherwise wouldn’t have noticed. “If you don’t notice an issue, there is no way to repair, or focus on it. [Executive coaching] is a very valuable tool.”

The Google Years

Merrill counts his best job working for someone else as his time as Chief Information Officer and Vice President of Engineering at Google, where he worked for six years from 1992-1998. Merrill discusses his experience at the tech giant as being highlighted by Google Founder Larry Page’s vision for a completely different kind of IPO that had never been done before. “Nobody could figure it out, and I came in and figured it out, Merrill continues, “I got to deal with everything – bankers, regulators, buyers – and also figure out this vision that Larry had. I think that’s an experience unlikely to be topped in my life.”

Merrill’s Google experience inculcated two main themes that continue today: the importance of a strong culture that maps the right messaging, and that reinforcing relationships is an important coaching tool. He defines company culture as those actions which the CEO and executives model every day, and the importance of that conduct being incentivized. “Some companies define cultural value as one thing, but incent on something else. In those situations people learn that the end result is what matters.” But, Merrill says, how you get there matters a great deal: “We pay very careful attention to the way we do things. We talk a lot about our culture, hold people accountable, and also commend appropriate action.”

Merrill learned the importance of reinforcing relationships from an encounter with Google’s then-CEO, Eric Schmidt. It was during the IPO period when Merrill had made a serious, expensive mistake for which he thought he’d be fired in front of the entire board of directors. Instead, Eric modeled a significant lesson when he pulled Merrill aside and, with his hand on his shoulder, said, “Douglas, I just need you to know that I love you, and don’t ever [expletive] do this again!” This combination of affirming the relationship without hiding the serious nature of the issue left a lasting impression on Merrill – the message being: Our relationship is intact, you just messed up.

An inside look at ZestFinance’s creative workspace

Merrill has carried his Schmidt lesson with him to ZestFinance, where relationships are very important to him, and has built the company with people he values. He encourages employees to be fully integrated with their family schedule, provides for six months or more maternity leave, supports attendance at school and community functions during the workday, and refuses to answer an email or phone call from anyone on vacation.

When asked his definition of success, Merrill explains that professionally, it’s about hiring good people and putting them in a culture where they can succeed, where radical diversity and radical communication give rise to beautiful problem-solving. Merrill’s definition of personal success revolves around his family – he pronounces the morning a success when he manages to coax hugs out of his young children before heading into Zest!